Enigma Emulator on the Commodore 64

By Michael Doornbos

- 23 minutes read - 4746 wordsIn The Math Behind Enigma we dug into the numbers. Why the Germans thought the machine was unbreakable and why the Allies proved them wrong. The theory is great, but there’s nothing quite like watching the algorithm run step by step on a machine that’s just barely fast enough to show you what’s happening.

We’re going to build a working Enigma M3 emulator on the Commodore 64. First in BASIC for clarity, then in 6502 assembly for speed. Three rotors selectable from the historical set of eight, the UKW-B reflector, and a configurable plugboard. The focus here is the algorithm, not a pretty UI. No animated rotors or blinking lamps. Just the raw cryptographic engine, as minimal as possible, so we can see exactly what the machine is doing at every step.

The M3 was the Kriegsmarine’s three-rotor machine, the one Bletchley Park spent most of the war cracking. It used the same mechanism as the earlier Wehrmacht Enigma I but expanded the rotor pool from five to eight, giving operators 336 possible rotor arrangements instead of 60.

The Signal Path

Every keypress takes the same journey through the machine. Press a letter, and the electrical signal follows this path:

Key → Plugboard → Right Rotor → Middle Rotor → Left Rotor

→ Reflector →

Left Rotor⁻¹ → Middle Rotor⁻¹ → Right Rotor⁻¹ → Plugboard → Lamp

The plugboard swaps pairs of letters at both ends. If A is plugged to Z, every A becomes Z (and vice versa) before and after the rotors touch it.

Each rotor is a scrambled alphabet. Going forward through a rotor uses the normal wiring. Coming back from the reflector, the signal passes through the same rotors in reverse, using the inverse mapping. If the forward wiring maps A to E, the inverse maps E back to A.

The reflector bounces the signal back without reversing it. This is what makes Enigma self-reciprocal: encrypt with the same settings and you get the plaintext back. It’s also what guarantees a letter never encrypts to itself, the fatal weakness the Allies exploited.

But the rotors aren’t static. They move.

Rotor Stepping

Before each letter is encrypted, the rotors step. The right rotor advances on every keypress, like an odometer’s ones digit. The middle rotor advances when the right rotor hits a notch position. The left rotor advances when the middle rotor hits a notch.

Simple enough. But the Enigma has a mechanical quirk called the double-step anomaly. When the middle rotor is at a notch position, pressing a key causes both the middle and left rotors to step, even though the middle rotor just arrived at that position on the previous keypress. The same pawl mechanism that pushes the left rotor also re-engages the middle rotor’s ratchet.

Here’s what it looks like with Rotors I-II-III starting at positions A-D-U:

Press Left Middle Right Notes

start A D U Starting positions

1 A D V Right steps

2 A E W Right was at V (III notch) → middle steps

3 B F X Middle at E (II notch) → double step!

On press 3, the middle rotor steps again even though it just moved to E. The middle and left rotors advance together.

One more wrinkle: Rotors I-V each have a single notch, but Rotors VI-VIII each have two notches (at Z and M). This means the middle rotor steps twice as often when a dual-notch rotor is in the right position, and the double-step anomaly can trigger at either notch.

In pseudocode:

before each keypress:

if middle rotor is at any of its notches:

step left rotor

step middle rotor ← the double step

else if right rotor is at any of its notches:

step middle rotor

always step right rotor

The Wiring

The historical rotor wirings were closely guarded secrets. Marian Rejewski deduced them mathematically before ever seeing a machine. Today they’re well documented. Here are all eight M3 rotors and the UKW-B reflector:

| Rotor | Wiring (A→…, B→…, C→…) | Notch(es) |

|---|---|---|

| I | EKMFLGDQVZNTOWYHXUSPAIBRCJ |

Q |

| II | AJDKSIRUXBLHWTMCQGZNPYFVOE |

E |

| III | BDFHJLCPRTXVZNYEIWGAKMUSQO |

V |

| IV | ESOVPZJAYQUIRHXLNFTGKDCMWB |

J |

| V | VZBRGITYUPSDNHLXAWMJQOFECK |

Z |

| VI | JPGVOUMFYQBENHZRDKASXLICTW |

Z and M |

| VII | NZJHGRCXMYSWBOUFAIVLPEKQDT |

Z and M |

| VIII | FKQHTLXOCBJSPDZRAMEWNIUYGV |

Z and M |

| UKW-B | YRUHQSLDPXNGOKMIEBFZCWVJAT |

n/a |

Reading the table: Rotor I maps A→E, B→K, C→M, D→F, and so on. The notch column shows which position(s) trigger the next rotor to step. Rotors VI-VIII with their dual notches were added by the Navy for the M3, making the stepping pattern less predictable.

For our code, we need these as numbers (A=0, B=1, … Z=25). We also need the inverse wiring for the return path through each rotor. The BASIC version computes the inverse tables at startup from the forward tables. One line does all the work:

420 RI(R,RF(R,I))=I

If the forward table says position 0 maps to 4, then the inverse table says position 4 maps to 0. The assembly version stores both forward and inverse tables as pre-computed data.

The Rotor Math

When a signal enters a rotor that’s been turned to position P, we need to account for the offset. Here’s what happens for input letter C:

entry = (C + P) mod 26 add position offset

result = rotor_table[entry] look up the wiring

output = (result - P + 26) mod 26 remove the offset

The + 26 before the final mod ensures we never go negative. This pattern repeats six times per character (three rotors forward, three rotors inverse) using the same math each time. Only the table and position change. That repetition makes it a natural fit for a subroutine in assembly.

What About Ring Settings?

If you’ve read about Enigma elsewhere, you’ve probably seen ring settings (Ringstellung). Each rotor had a movable ring that shifted the notch positions and the alphabet visible through the window, without changing the internal wiring. In practice, ring settings offset the relationship between the rotor’s position and its wiring by a fixed amount.

We’re leaving them out. The core algorithm is the same with or without ring settings. They just add a per-rotor offset that gets applied during the entry/exit math and shifts the notch positions. It’s a few extra subtractions, not a new concept. What they do add is another 17,576 possible settings (26 x 26 x 26), which made the operator’s key sheets more complex but doesn’t teach us anything new about how the machine works.

If you want to add them later, it’s a straightforward extension. The Extra Credit section at the end has some pointers.

BASIC Version

This runs on any Commodore 8-bit machine with no extensions. You pick three rotors from I-VIII, set starting positions, optionally configure plugboard pairs, and type your message. The same program encrypts and decrypts. Just use the same settings, because that’s how Enigma works.

We’re keeping these as simple as possible. No input validation, no error handling, no hand-holding. If you type lowercase or numbers, you’ll get garbage out. The real Enigma only had 26 keys and all input must be uppercase A-Z. You’re a sophisticated person. You can handle that.

5 PRINT CHR$(5)

10 PRINT CHR$(147);" ENIGMA M3 EMULATOR"

20 PRINT " KRIEGSMARINE ENIGMA":PRINT

100 DIM RF(7,25),RI(7,25),RE(25),PB(25)

110 FOR R=0 TO 7:FOR I=0 TO 25

120 READ RF(R,I):NEXT I,R

200 DATA 4,10,12,5,11,6,3,16,21,25

210 DATA 13,19,14,22,24,7,23,20,18,15

220 DATA 0,8,1,17,2,9

230 DATA 0,9,3,10,18,8,17,20,23,1

240 DATA 11,7,22,19,12,2,16,6,25,13

250 DATA 15,24,5,21,14,4

260 DATA 1,3,5,7,9,11,2,15,17,19

270 DATA 23,21,25,13,24,4,8,22,6,0

280 DATA 10,12,20,18,16,14

290 DATA 4,18,14,21,15,25,9,0,24,16

300 DATA 20,8,17,7,23,11,13,5,19,6

310 DATA 10,3,2,12,22,1

320 DATA 21,25,1,17,6,8,19,24,20,15

330 DATA 18,3,13,7,11,23,0,22,12,9

340 DATA 16,14,5,4,2,10

350 DATA 9,15,6,21,14,20,12,5,24,16

360 DATA 1,4,13,7,25,17,3,10,0,18

370 DATA 23,11,8,2,19,22

380 DATA 13,25,9,7,6,17,2,23,12,24

390 DATA 18,22,1,14,20,5,0,8,21,11

395 DATA 15,4,10,16,3,19

400 DATA 5,10,16,7,19,11,23,14,2,1

410 DATA 9,18,15,3,25,17,0,12,4,22

420 DATA 13,8,20,24,6,21

450 REM COMPUTE INVERSE TABLES

460 FOR R=0 TO 7:FOR I=0 TO 25

470 RI(R,RF(R,I))=I

480 NEXT I,R

500 REM REFLECTOR UKW-B

510 FOR I=0 TO 25:READ RE(I):NEXT

520 DATA 24,17,20,7,16,18,11,3,15,23

530 DATA 13,6,14,10,12,8,4,1,5,25

540 DATA 2,22,21,9,0,19

600 REM NOTCH POSITIONS (TWO PER ROTOR)

610 DIM NO(7,1)

620 NO(0,0)=16:NO(0,1)=-1

630 NO(1,0)=4:NO(1,1)=-1

640 NO(2,0)=21:NO(2,1)=-1

650 NO(3,0)=9:NO(3,1)=-1

660 NO(4,0)=25:NO(4,1)=-1

670 NO(5,0)=25:NO(5,1)=12

680 NO(6,0)=25:NO(6,1)=12

690 NO(7,0)=25:NO(7,1)=12

695 REM INIT PLUGBOARD (IDENTITY)

700 FOR I=0 TO 25:PB(I)=I:NEXT

710 PRINT "SELECT 3 ROTORS (1-8)"

720 INPUT "LEFT ROTOR";RL

730 INPUT "MIDDLE ROTOR";RM

740 INPUT "RIGHT ROTOR";RR

750 RL=RL-1:RM=RM-1:RR=RR-1

760 INPUT "START POSITIONS (AAA)";PO$

770 LP=ASC(MID$(PO$,1,1))-65

780 MP=ASC(MID$(PO$,2,1))-65

790 RP=ASC(MID$(PO$,3,1))-65

800 INPUT "PLUGBOARD PAIRS (0=NONE)";NP

810 IF NP=0 THEN 860

820 FOR I=1 TO NP

830 PRINT "PAIR";I;

840 INPUT "(E.G. AB)";PP$

845 A=ASC(MID$(PP$,1,1))-65

850 B=ASC(MID$(PP$,2,1))-65

855 PB(A)=B:PB(B)=A:NEXT

860 INPUT "MESSAGE";MS$

870 PRINT "OUTPUT: ";

900 FOR CH=1 TO LEN(MS$)

910 GOSUB 2000

920 C=ASC(MID$(MS$,CH,1))-65

930 C=PB(C)

940 GOSUB 3000

950 C=PB(C)

960 PRINT CHR$(C+65);

970 NEXT

980 PRINT:END

2000 REM STEP ROTORS

2010 IF MP<>NO(RM,0)ANDMP<>NO(RM,1) THEN 2040

2020 LP=LP+1:LP=LP-INT(LP/26)*26

2030 MP=MP+1:MP=MP-INT(MP/26)*26

2040 IF RP<>NO(RR,0)ANDRP<>NO(RR,1) THEN 2060

2050 MP=MP+1:MP=MP-INT(MP/26)*26

2060 RP=RP+1:RP=RP-INT(RP/26)*26

2070 RETURN

3000 REM FORWARD THROUGH ROTORS

3010 E=(C+RP):E=E-INT(E/26)*26

3020 C=RF(RR,E)

3030 C=(C-RP+26):C=C-INT(C/26)*26

3040 E=(C+MP):E=E-INT(E/26)*26

3050 C=RF(RM,E)

3060 C=(C-MP+26):C=C-INT(C/26)*26

3070 E=(C+LP):E=E-INT(E/26)*26

3080 C=RF(RL,E)

3090 C=(C-LP+26):C=C-INT(C/26)*26

3100 REM REFLECTOR

3110 C=RE(C)

3120 REM INVERSE THROUGH ROTORS

3130 E=(C+LP):E=E-INT(E/26)*26

3140 C=RI(RL,E)

3150 C=(C-LP+26):C=C-INT(C/26)*26

3160 E=(C+MP):E=E-INT(E/26)*26

3170 C=RI(RM,E)

3180 C=(C-MP+26):C=C-INT(C/26)*26

3190 E=(C+RP):E=E-INT(E/26)*26

3200 C=RI(RR,E)

3210 C=(C-RP+26):C=C-INT(C/26)*26

3220 RETURN

The DATA statements in lines 200-420 are the numeric equivalents of the rotor wiring table, all eight rotors read sequentially, 26 values each. Lines 450-480 compute every inverse table with that one-line trick. The reflector goes into

RE() at lines 510-540.

The notch table at lines 610-690 stores two values per rotor. Rotors I-V use -1 as a sentinel for their unused second notch. Since rotor positions are always 0-25, the comparison MP<>-1 is always true, so the second notch is effectively ignored. Rotors VI-VIII get both Z(25) and M(12).

Lines 2000-2070 handle stepping with the double-step logic. The AND in lines 2010 and 2040 checks both notch positions: we only skip the step if the position matches neither notch. We use the same modulo-without-a-cartridge technique from the Vigenere article: X-INT(X/26)*26 gives us X mod 26 without needing Simon’s BASIC or any extensions.

The subroutine at 3000 is where the real work happens. For each rotor, the pattern is:

- Add the rotor’s position to the input:

E=(C+RP) - Mod 26 to wrap:

E=E-INT(E/26)*26 - Look up the wiring:

C=RF(RR,E) - Subtract the position:

C=(C-RP+26) - Mod 26 again:

C=C-INT(C/26)*26

Six rotor passes (three forward, three inverse) plus the reflector lookup, twelve mod operations, and you’ve encrypted one letter. On a 1 MHz machine doing all this in interpreted BASIC, you can watch each character appear one at a time. That’s the beauty of doing cryptography on slow hardware. The algorithm has nowhere to hide.

Assembly Version

The assembly version follows the same algorithm but replaces array lookups with direct memory addressing and eliminates division entirely. Written for Turbo Macro Pro, assembled and run right on the C64. It’ll also run with minor syntax changes in cross-assemblers like TMPx, Kick Assembler, and ACME if you prefer to assemble on a modern machine.

mod26

In the Vigenere and RC4 articles we used a 24-bit division routine for modulus. Here’s the fun part. We don’t need division at all. Every value we ever mod by 26 is already between 0 and 51 (the sum of two values each 0-25). So mod 26 is just a comparison and a subtract:

mod26 cmp #26

bcc done ; already < 26

sbc #26 ; subtract once

done rts

Two instructions in the common case, four in the worst. No division routine, no multi-byte arithmetic. This alone makes the assembly version much cleaner than the RC4 implementation.

The Rotor Pass

Every rotor, forward or inverse, uses the same entry/exit math. The only difference is which 26-byte table we look up and which position offset we apply. One subroutine handles all twelve passes per character:

; Input: A = letter (0-25)

; X = rotor position (0-25)

; ptr ($50/$51) = rotor table address

; Output: A = result (0-25)

rotor_pass

stx temp ; save position

clc

adc temp ; entry = letter + position

jsr mod26

tay

lda (ptr),y ; table lookup

sec

sbc temp ; exit = result - position

clc

adc #26 ; ensure positive

jsr mod26

rts

The key is indirect indexed addressing: lda (ptr),y. The 2-byte pointer at $50/$51 tells the 6502 which rotor table to use, and Y holds the offset into that table. To switch rotors, we just change the pointer.

Address lookup tables make rotor selection fast:

fwd_lo .byte <rot1_f,<rot2_f,<rot3_f,<rot4_f

.byte <rot5_f,<rot6_f,<rot7_f,<rot8_f

fwd_hi .byte >rot1_f,>rot2_f,>rot3_f,>rot4_f

.byte >rot5_f,>rot6_f,>rot7_f,>rot8_f

Loading Rotor III’s forward table into the pointer takes four instructions:

set_fwd ldy fwd_lo,x ; preserves A

sty ptr

ldy fwd_hi,x

sty ptr+1

rts

We use Y instead of A here so the current letter value in A survives the table switch. Small detail, but it lets the encrypt routine chain rotor passes without saving and restoring A between each one.

Stepping

The step routine checks the double-step condition first, then normal middle advance, then always steps right. With the M3’s dual-notch rotors (VI-VIII), we check two notch positions per rotor:

step

; Double step: middle at either notch?

ldx mid_sel

lda mid_pos

cmp notch1,x

beq do_double

cmp notch2,x

bne no_double

do_double

; Step left and middle

lda left_pos

clc

adc #1

jsr mod26

sta left_pos

lda mid_pos

clc

adc #1

jsr mod26

sta mid_pos

jmp step_right

no_double

; Normal: right at either notch?

ldx right_sel

lda right_pos

cmp notch1,x

beq do_mid

cmp notch2,x

bne step_right

do_mid

lda mid_pos

clc

adc #1

jsr mod26

sta mid_pos

step_right

; Always step right

lda right_pos

clc

adc #1

jsr mod26

sta right_pos

rts

Two notch tables (notch1 and notch2) store the turnover positions. For Rotors I-V with a single notch, the second table holds $ff (255), which no valid position (0-25) will ever match. For Rotors VI-VIII, both entries are live.

The Full Listing

Here’s the complete emulator. It assembles at $C000 and runs with SYS 49152. The demo encrypts “AAAAA” with Rotors I-II-III at positions AAA, our test vector. It prints the configuration and both input and output so you can see what it’s doing.

Note that TMP’s .text and .null directives encode as screen codes, not PETSCII, so all display strings use .byte with explicit PETSCII values. The comments above each string show what they say. If you’re using a cross-assembler like ACME or Kick Assembler, you can use their native string directives instead.

; ==============================

; enigma m3 - commodore 64

; kriegsmarine, rotors i-viii

; ukw-b reflector

; turbo macro pro / tmpx

; by michael doornbos 2026

; mike@imapenguin.com

;

; .null/.text = screen codes

; use .byte for petscii strings

; ==============================

* = $c000

; --- zero page ---

; ptr = table pointer (2 bytes)

ptr = $50

right_pos = $fb

mid_pos = $fc

left_pos = $fd

temp = $fe

chrout = $ffd2

; --- entry point ---

; cls, white text

lda #$93

jsr chrout

lda #5

jsr chrout

lda #13

jsr chrout

ldx #<s_title

ldy #>s_title

jsr print

lda #13

jsr chrout

ldx #<s_sub

ldy #>s_sub

jsr print

lda #13

jsr chrout

lda #13

jsr chrout

; show rotors

ldx #<s_rotor

ldy #>s_rotor

jsr print

ldx left_sel

jsr print_rn

ldx #<s_sep

ldy #>s_sep

jsr print

ldx mid_sel

jsr print_rn

ldx #<s_sep

ldy #>s_sep

jsr print

ldx right_sel

jsr print_rn

lda #13

jsr chrout

; show positions

ldx #<s_start

ldy #>s_start

jsr print

lda init_lpos

clc

adc #65

jsr chrout

ldx #<s_sep

ldy #>s_sep

jsr print

lda init_mpos

clc

adc #65

jsr chrout

ldx #<s_sep

ldy #>s_sep

jsr print

lda init_rpos

clc

adc #65

jsr chrout

lda #13

jsr chrout

lda #13

jsr chrout

; show input

ldx #<s_input

ldy #>s_input

jsr print

ldx #0

pmsgloop lda message,x

beq pmsgdone

stx temp

jsr chrout

ldx temp

inx

jmp pmsgloop

pmsgdone lda #13

jsr chrout

; output label

ldx #<s_out

ldy #>s_out

jsr print

; init positions

lda init_rpos

sta right_pos

lda init_mpos

sta mid_pos

lda init_lpos

sta left_pos

; encrypt each char

ldx #0

msgloop lda message,x

beq msgdone

stx savex

sec

; a=0..z=25

sbc #65

jsr encrypt

clc

adc #65

jsr chrout

ldx savex

inx

jmp msgloop

msgdone lda #13

jsr chrout

rts

savex .byte 0

; "aaaaa"

message .byte 65,65,65,65,65,0

; --- configuration ---

; select (0=i, 7=viii)

right_sel .byte 2 ; iii

mid_sel .byte 1 ; ii

left_sel .byte 0 ; i

; positions (0=a, 25=z)

init_rpos .byte 0

init_mpos .byte 0

init_lpos .byte 0

; notch positions per rotor

; $ff = no second notch

notch1 .byte 16,4,21,9

.byte 25,25,25,25

notch2 .byte $ff,$ff,$ff,$ff

.byte $ff,12,12,12

; --- strings (petscii) ---

; " enigma m3 emulator"

s_title .byte 32,32,69,78,73,71

.byte 77,65,32,77,51,32

.byte 69,77,85,76,65,84

.byte 79,82,0

; " kriegsmarine enigma"

s_sub .byte 32,32,75,82,73,69

.byte 71,83,77,65,82,73

.byte 78,69,32,69,78,73

.byte 71,77,65,0

; " rotors: "

s_rotor .byte 32,32,82,79,84,79

.byte 82,83,58,32,32,0

; " start: "

s_start .byte 32,32,83,84,65,82

.byte 84,58,32,32,32,0

; " input: "

s_input .byte 32,32,73,78,80,85

.byte 84,58,32,32,32,0

; " output: "

s_out .byte 32,32,79,85,84,80

.byte 85,84,58,32,32,0

; " - "

s_sep .byte 32,45,32,0

; rotor names (petscii)

rn1 .byte 73,0

rn2 .byte 73,73,0

rn3 .byte 73,73,73,0

rn4 .byte 73,86,0

rn5 .byte 86,0

rn6 .byte 86,73,0

rn7 .byte 86,73,73,0

rn8 .byte 86,73,73,73,0

rn_lo .byte <rn1,<rn2

.byte <rn3,<rn4

.byte <rn5,<rn6

.byte <rn7,<rn8

rn_hi .byte >rn1,>rn2

.byte >rn3,>rn4

.byte >rn5,>rn6

.byte >rn7,>rn8

; --- print string ---

; x=lo, y=hi

print stx ptr

sty ptr+1

ldy #0

ploop lda (ptr),y

beq pdone

jsr chrout

iny

bne ploop

pdone rts

; --- print rotor name ---

; x = rotor index (0-7)

print_rn

lda rn_lo,x

sta ptr

lda rn_hi,x

sta ptr+1

ldy #0

rnloop lda (ptr),y

beq rndone

jsr chrout

iny

bne rnloop

rndone rts

; --- encrypt ---

; a = letter (0-25) in/out

encrypt pha

jsr step

pla

; plugboard in

tax

lda plugboard,x

; right fwd

ldx right_sel

jsr set_fwd

ldx right_pos

jsr rotor_pass

; middle fwd

ldx mid_sel

jsr set_fwd

ldx mid_pos

jsr rotor_pass

; left fwd

ldx left_sel

jsr set_fwd

ldx left_pos

jsr rotor_pass

; reflector

tax

lda reflector,x

; left inv

ldx left_sel

jsr set_inv

ldx left_pos

jsr rotor_pass

; middle inv

ldx mid_sel

jsr set_inv

ldx mid_pos

jsr rotor_pass

; right inv

ldx right_sel

jsr set_inv

ldx right_pos

jsr rotor_pass

; plugboard out

tax

lda plugboard,x

rts

; --- step rotors ---

step

; double step?

ldx mid_sel

lda mid_pos

cmp notch1,x

beq do_double

cmp notch2,x

bne no_double

do_double

; step left+mid

lda left_pos

clc

adc #1

jsr mod26

sta left_pos

lda mid_pos

clc

adc #1

jsr mod26

sta mid_pos

jmp step_right

no_double

; right at notch?

ldx right_sel

lda right_pos

cmp notch1,x

beq do_mid

cmp notch2,x

bne step_right

do_mid

lda mid_pos

clc

adc #1

jsr mod26

sta mid_pos

step_right

; always step right

lda right_pos

clc

adc #1

jsr mod26

sta right_pos

rts

; --- mod26 ---

mod26 cmp #26

bcc m26done

sbc #26

m26done rts

; --- rotor pass ---

rotor_pass

stx temp

clc

adc temp

jsr mod26

tay

lda (ptr),y

sec

sbc temp

clc

adc #26

jsr mod26

rts

; --- set table pointer ---

set_fwd ldy fwd_lo,x

sty ptr

ldy fwd_hi,x

sty ptr+1

rts

set_inv ldy inv_lo,x

sty ptr

ldy inv_hi,x

sty ptr+1

rts

; --- address tables ---

fwd_lo .byte <rot1_f,<rot2_f

.byte <rot3_f,<rot4_f

.byte <rot5_f,<rot6_f

.byte <rot7_f,<rot8_f

fwd_hi .byte >rot1_f,>rot2_f

.byte >rot3_f,>rot4_f

.byte >rot5_f,>rot6_f

.byte >rot7_f,>rot8_f

inv_lo .byte <rot1_i,<rot2_i

.byte <rot3_i,<rot4_i

.byte <rot5_i,<rot6_i

.byte <rot7_i,<rot8_i

inv_hi .byte >rot1_i,>rot2_i

.byte >rot3_i,>rot4_i

.byte >rot5_i,>rot6_i

.byte >rot7_i,>rot8_i

; === rotor wiring ===

; i: ekmflgdqvzntowyhxuspaibrcj

rot1_f .byte 4,10,12,5,11,6

.byte 3,16,21,25,13,19

.byte 14,22,24,7,23,20

.byte 18,15,0,8,1,17

.byte 2,9

; ii: ajdksiruxblhwtmcqgznpyfvoe

rot2_f .byte 0,9,3,10,18,8

.byte 17,20,23,1,11,7

.byte 22,19,12,2,16,6

.byte 25,13,15,24,5,21

.byte 14,4

; iii: bdfhjlcprtxvznyeiwgakmusqo

rot3_f .byte 1,3,5,7,9,11

.byte 2,15,17,19,23,21

.byte 25,13,24,4,8,22

.byte 6,0,10,12,20,18

.byte 16,14

; iv: esovpzjayquirhxlnftgkdcmwb

rot4_f .byte 4,18,14,21,15,25

.byte 9,0,24,16,20,8

.byte 17,7,23,11,13,5

.byte 19,6,10,3,2,12

.byte 22,1

; v: vzbrgityupsdnhlxawmjqofeck

rot5_f .byte 21,25,1,17,6,8

.byte 19,24,20,15,18,3

.byte 13,7,11,23,0,22

.byte 12,9,16,14,5,4

.byte 2,10

; vi: jpgvoumfyqbenhzrdkasxlictw

rot6_f .byte 9,15,6,21,14,20

.byte 12,5,24,16,1,4

.byte 13,7,25,17,3,10

.byte 0,18,23,11,8,2

.byte 19,22

; vii: nzjhgrcxmyswboufaivlpekqdt

rot7_f .byte 13,25,9,7,6,17

.byte 2,23,12,24,18,22

.byte 1,14,20,5,0,8

.byte 21,11,15,4,10,16

.byte 3,19

; viii: fkqhtlxocbjspdzramewniuygv

rot8_f .byte 5,10,16,7,19,11

.byte 23,14,2,1,9,18

.byte 15,3,25,17,0,12

.byte 4,22,13,8,20,24

.byte 6,21

; inverse tables

rot1_i .byte 20,22,24,6,0,3

.byte 5,15,21,25,1,4

.byte 2,10,12,19,7,23

.byte 18,11,17,8,13,16

.byte 14,9

rot2_i .byte 0,9,15,2,25,22

.byte 17,11,5,1,3,10

.byte 14,19,24,20,16,6

.byte 4,13,7,23,12,8

.byte 21,18

rot3_i .byte 19,0,6,1,15,2

.byte 18,3,16,4,20,5

.byte 21,13,25,7,24,8

.byte 23,9,22,11,17,10

.byte 14,12

rot4_i .byte 7,25,22,21,0,17

.byte 19,13,11,6,20,15

.byte 23,16,2,4,9,12

.byte 1,18,10,3,24,14

.byte 8,5

rot5_i .byte 16,2,24,11,23,22

.byte 4,13,5,19,25,14

.byte 18,12,21,9,20,3

.byte 10,6,8,0,17,15

.byte 7,1

rot6_i .byte 18,10,23,16,11,7

.byte 2,13,22,0,17,21

.byte 6,12,4,1,9,15

.byte 19,24,5,3,25,20

.byte 8,14

rot7_i .byte 16,12,6,24,21,15

.byte 4,3,17,2,22,19

.byte 8,0,13,20,23,5

.byte 10,25,14,18,11,7

.byte 9,1

rot8_i .byte 16,9,8,13,18,0

.byte 24,3,21,10,1,5

.byte 17,20,7,12,2,15

.byte 11,4,22,25,19,6

.byte 23,14

; ukw-b: yruhqsldpxngokmiebfzcwvjat

reflector .byte 24,17,20,7,16,18

.byte 11,3,15,23,13,6

.byte 14,10,12,8,4,1

.byte 5,25,2,22,21,9

.byte 0,19

; plugboard (identity = no swaps)

plugboard .byte 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9

.byte 10,11,12,13,14,15

.byte 16,17,18,19,20,21

.byte 22,23,24,25

With the display code, string data, and rotor name lookup tables, the whole thing comes in around 1.1 KB. The rotor wiring tables (forward and inverse for all eight rotors, plus the reflector and plugboard) account for about 500 bytes of that. The actual encryption logic is still under 200 bytes.

To change the configuration, modify the bytes at right_sel, mid_sel, and left_sel (0-7 for Rotors I-VIII), set starting positions in init_rpos/init_mpos/init_lpos (0-25 for A-Z), and edit the plugboard table to swap pairs. Or write a BASIC front-end that POKEs these values before calling SYS 49152.

Testing

The standard test vector works for the M3 just as it did for the Enigma I since the M3 is a superset. Rotors I-II-III, reflector UKW-B, no plugboard, all starting positions at A. Encrypt AAAAA and you should get BDZGO.

Both versions produce this output. If yours doesn’t, check your rotor data first. One wrong number in a DATA statement will throw everything off.

Verify Against a Known Implementation

Before trusting your own code, check it against something known to work. Two good options:

101 Computing Enigma Emulator is a browser-based emulator that replicates the M3 with a UKW-B reflector, exactly what we built. To match our test vector:

- Set the rotors to I - II - III (left to right) using the rotor selectors

- Click each rotor wheel until all three show A

- Leave the plugboard empty (no cables connected)

- Click the letter A five times on the keyboard

- The lamp panel should light up B, then D, Z, G, O

If you want to test the self-inverse property, reset all rotors back to A-A-A and type B-D-Z-G-O. You should get A-A-A-A-A back.

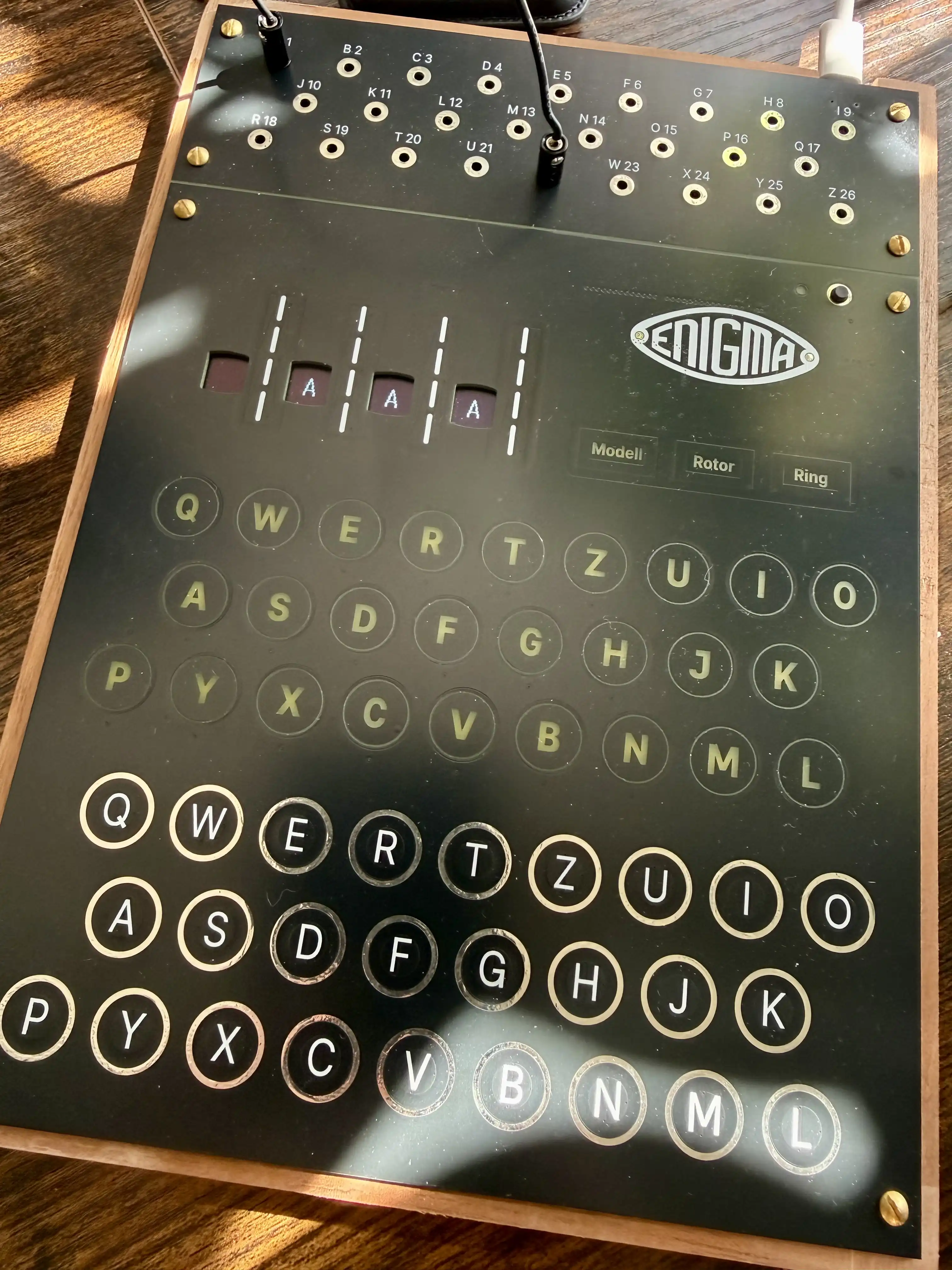

Enigma Touch: If you have one of these, it’s the most satisfying way to verify. It produces historically accurate output compatible with real Enigma machines.

- Press the Modell button and select M3

- Use the rotor sliders to select rotors I, II, III

- Set all ring settings to A (or 01)

- Slide each rotor position to A

- Make sure no plugboard cables are connected

- Press A-A-A-A-A on the capacitive keyboard and the lamps should spell out BDZGO

The Enigma Touch also makes it easy to test the plugboard and dual-notch rotors. Plug in a few cables, type the same message, and compare the output to what your C64 produces with the same plugboard configuration. Any mismatch means a bug in your code.

Self-Inverse

Enigma’s party trick is that encryption and decryption are the same operation. Reset the rotors to AAA, feed BDZGO back in, and you get AAAAA. This works because the reflector makes the circuit symmetric. The electrical path from A to B is the same as the path from B to A.

Try encrypting HELLO with any settings, then reset to those same settings and encrypt the result. You’ll get HELLO back. This is the property that made Enigma practical in the field. Operators didn’t need separate encrypt and decrypt procedures. It’s pretty satisfying to see it work on actual hardware.

Double-Step Verification

To verify the double-step anomaly is implemented correctly, set Rotors I-II-III to starting positions A-D-U (that’s LP=0, MP=3, RP=20 in the code). Encrypt three letters and watch the positions change:

After letter 1: A-D-V (right stepped)

After letter 2: A-E-W (right was at V, middle stepped)

After letter 3: B-F-X (middle was at E, double step!)

If the third step gives you A-F-X instead of B-F-X, the double-step logic is wrong. The left rotor should have advanced.

Plugboard Test

To test the plugboard, try the same Rotors I-II-III at AAA but add plugboard pairs. With A swapped with B (PB(0)=1, PB(1)=0 in BASIC, or edit the plugboard table in assembly), encrypting AAAAA should give a completely different result than BDZGO. The plugboard scrambles the signal before and after the rotors, so even one pair changes everything.

Dual-Notch Test

To verify the dual-notch stepping works for Rotors VI-VIII, put Rotor VI in the right position and step through its turnovers. With the right rotor at position L (11), the next step to M (12) should trigger the middle rotor to advance. That’s the M notch. Continuing to Z (25), the Z notch should trigger it again. If only one of those turnovers fires, the dual-notch check is broken.

Cross-Verification

Both the BASIC and assembly versions should produce identical output for the same settings and input. If they don’t, the bug is almost certainly in your data tables. Those inverse rotor tables are easy to get wrong by hand. The BASIC version computes them automatically, which is a good way to double-check the assembly version’s pre-computed tables.

Benchmarks

The speed difference between the two versions is dramatic but not surprising. BASIC has to parse each line, do floating-point division for every mod operation, and navigate two-dimensional arrays with interpreted index arithmetic. The assembly version does table lookups and simple comparisons.

Rough measurements with a longer message:

| Version | Speed |

|---|---|

| BASIC | ~3 characters/sec |

| Assembly | ~1,500 characters/sec |

That’s roughly a 500x speedup, in the same ballpark as the RC4 comparison. The assembly version encrypts fast enough that output appears instantaneous for any reasonable message length. The BASIC version lets you watch each letter appear, which is its own kind of reward.

The bottleneck in BASIC isn’t the algorithm. It’s the language. Each of those twelve E=E-INT(E/26)*26 mod operations involves floating-point division on a processor with no hardware multiply, let alone divide. The assembly version replaces all of it with cmp #26 / bcc / sbc #26. Sometimes the simplest optimization is just picking the right tool.

Extra Credit

We implemented the Enigma M3 with three rotors from eight, one reflector, plugboard, and dual notches. But there’s more to explore if you want to keep going:

-

Ring settings: Each real Enigma rotor had an adjustable ring that shifted the relationship between the wiring and the visible letter. Adding ring settings means adjusting the notch positions and the entry/exit offsets by a per-rotor ring value. It’s not hard, but it multiplies the keyspace by another 17,576.

-

Interactive mode: Write a BASIC wrapper that lets you type one letter at a time with immediate output, like the real machine. The assembly encrypt routine is fast enough to feel instantaneous. Just

SYS 49152with a single character POKE’d into the message buffer. -

Navy M4: The M4 added a fourth thin rotor (Beta or Gamma) and a thin reflector. The algorithm is identical, you just need more rotor data and an additional pass through the fourth rotor. This was the machine that caused the famous ten-month blackout at Bletchley Park.

-

Optimize the assembly: The

rotor_passsubroutine callsmod26twice viajsr. Inlining those comparisons would save 12 cycles per rotor pass, or 72 cycles per character. For bulk encryption of long messages, that adds up. -

Cross-platform: The BASIC version should run on a VIC-20, Plus/4, or C128 without changes. Try it. The assembly version needs only the

chrout = $ffd2Kernal call, which is the same on all Commodore 8-bit machines.

Having Fun With It

Once you’ve got the test vector working, try something more interesting. Set up Rotors I-II-III at AAA with no plugboard and encrypt this:

AREYOUKEEPINGUPWITHTHECOMMODORE

BECAUSETHECOMMODOREISKEEPINGUP

WITHYOU

You should get:

BCCVAPEYWLBMHWDTYIJSWPWAYCWWJ

MUQRPFXEQXFWPXTDCKDKVYLRXYWMZ

ZHWVLARHJH

Now reset the rotors back to AAA and feed that ciphertext back in. Out comes the original message. Same settings, same operation, plaintext restored. That’s the whole trick: the reflector makes the circuit symmetric, so there’s no difference between encrypt and decrypt. A field operator only needed to know one procedure.

The assembly version handles 68 characters so fast you won’t see it happen. The BASIC version takes about 20 seconds, just long enough to watch each letter appear and appreciate what the machine is doing under the hood.